Nostalgia Fever

Do we need more cowbell? Or antibotics?

I’m excited to share another collaboration between Coby Dolloff and myself. You can read our first essay together here: “Steinbeck, Aristotle, and the Language of Sports.” Unlike in our previous essay, we haven’t divided this one into distinctive sections. So we’ll let you—the readers—parse out who is who (hint: the great meme is Coby, of course).

We recently rang in the New Year, and the sublimely haunting standard New Year’s tune keeps ringing through my head.

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot

And days of auld lang syne?

Burns’s famous phrase translates to “old long since” — roughly, times gone by. In a fitting reflection for the New Year, he is asks, “Should we forget the old days? Should we forget the nostalgia and move on?”

The cultural winds seem to answer with a resounding no!

Nostalgia is all the rage these days. Teens are riding around on bikes Stranger-Things-style. They’re rewatching Disney movies. They’re buying old DVD players. They’re running toward the analog at neck-break speed (except when it comes to their homework, unfortunately). Dumb phones have become status symbols. I just bought a polaroid camera. Josh Nadeau recently asked, with characteristic honest simplicity, “What will it take to bring the world back to 1996?”

None of this desire for the old is really new. We’ve been wishing for old times since before time began.

I can’t help but think of a characteristic bit of Chesterton. As is often the case with his best stuff, it comes buried deep within an obscure work: his 1904 biography of the minor painter G.F. Watts. He muses:

The desperate modern talk about dark days and reeling altars, and the end of Gods and angels, is the oldest talk in the world: lamentations over the growth of agnosticism can be found in the monkish sermons of the dark ages; horror at youthful impiety can be found in the Iliad.

The more things change, as the proverb goes, the more they stay the same.

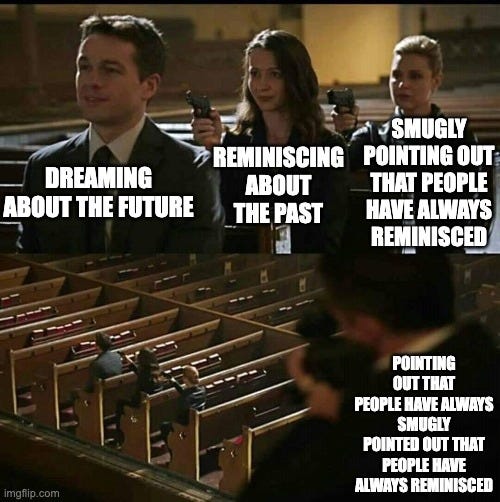

However, there are some who act as if the perennial nature of this tendency makes it inherently ridiculous. There are some who point out (with obvious disdain) that “people have always been nostalgic for approximately one generation ago” — as if this automatically invalidates such nostalgia. As if shouting “recency bias!” loudly enough counts as an argument.

Among the many antidotes to counteract this line of thinking is that it also applies to itself: if people have always been nostalgic for one generation past, people have always been dismissive of them for always having done so.

The fact that humans have engaged in certain similar behaviors throughout history does not invalidate that behavior. Food, song, sport, romance, religion, and all their compatriots beg to differ.

But if nostalgia is not foolish naivety (as I surmise), what is it?

What does it say about us?

What does it mean?

I suspect that nostalgia (especially our current frenzy) is a double-edged sword, indicative of (at least) two phenomena. The first is a certain dissatisfaction with modernity. We are no longer enamored by the whatever-version-of-the-new-iphone. We have become acutely dissatisfied with what philosopher Byung-Chul Han might call the “smooth aesthetic,” the frictionless egocentric design that digital devices offer.

When someone reminisces about DVD players, there is the trace of the tactile: that feeling of selecting, opening, cleaning, and placing the disc just perfectly into the outstretched circular receiver. When someone posts a gallery of 90s fashion, there is the trace of the idiosyncratic: the bright colors and designs that are so dissimilar to today’s monochromatic and singular trends.

Oddly enough, we can even be nostalgic about times that we never experienced. As Eddie LaRow recently pointed out in First Things, the surge of nostalgia is largely driven by Gen-Z: “a generation that had never lived in the 1980s’ or ’90s suddenly longed for it.”

Like fantasy, like comedy, like prophecy — like all things that are truer than facts — nostalgia reminds us that things can (and may) be other than they are. Nostalgia becomes a helpful barometer. In our case, it points toward the analogue and human, refusing techo-optimism’s demands for a blank check. This is a good thing.

For T.S. Eliot, nostalgia functions as a tutor, instructing our loves past possession and towards that which is beyond our grasp:

This is the use of memory:

For liberation - not less of love but expanding

Of love beyond desire, and so liberation

From the future as well as the past.1

Perhaps what we reach for has always been ungraspable, at least on this side of things, but perhaps there is something good in the grasping. He writes elsewhere:

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again.2

There is something magical about rose-colored lenses.

Conversely, nostalgia can become a type of blindness or abdication of responsibility, a yearning for carefree adolescence. Carl Jung acutely connected this desire to a real social danger. In his essay, “The Undiscovered Self,” Jung discusses the intersection of individual and collective psychology, sketching (among other things) the emergence of Fascism in the 20th century.3

Discussing the allure of mass movements, Jung comments:

Where the many are, there is security; what the many believe must of course be true; what the many want must be worth striving for, and necessary, and therefore good. In the clamour of the many resides the power to snatch wish-fulfilments by force; sweetest of all, however, is that gentle and painless slipping back into the kingdom of childhood, into the paradise of parental care, into happy-go-luckiness and irresponsibility. All the thinking and looking after are done from the top; to all questions there is an answer, and for all needs the necessary provision is made. The infantile dream-state of the mass man is so unrealistic that he never thinks to ask who is paying for this paradise. The balancing of accounts is left to a higher political or social authority, which welcomes the task, for its power is thereby increased; and the more power it has, the weaker and more helpless the individual becomes.

There are essays to be written about this fecund, dense quotation, but I want to draw our attention to the way it illuminates the dark side of nostalgia. In its worst form, nostalgia is a desire for the “gentle and painless slipping back into the kingdom of childhood.” It avoids the existential difficulty of choice and offloads responsibility to another. Is this more comfortable? Sure. All of our moral, ethical, religious, philosophical, and political questions are punted elsewhere.

This imagined world lacks of the messiness of human life. It gives facile (ie. ideological) answers and ties up any loose ends. It creates a world where all our problems are solved in the past. And if we can just go back, we can set up a comfy pillow-fort and gorge ourselves on Oreos (wish fulfillment 101).

Nostalgia is brilliant at projecting this false completeness and ease. The rose-colored glasses can be used as a coping mechanism, a defense strategy, an existential flight from ourselves and the present world.

However, this disastrous course is (as often the case) driven by a good desire. We desire a true safety and goodness; a remedy for the broken present; a world in which everything sad will come untrue. Somewhere deep in my soul is a story — a story in which long, long ago we lost something in a terrible bargain, something that we have never quite been able to get back ever since.

My mind drifts back to that same obscure bit of Chesterton. In that passage, he is not talking about nostalgia, but about hope:

But what does the word “hope” represent? It represents only a broken instantaneous glimpse of something that is immeasurably older and wilder than language, that is immeasurably older and wilder than man; a mystery to saints and a reality to wolves. . . something for which there is neither speech nor language, which has been too vast for any eye to see and too secret for any religion to utter, even as an esoteric doctrine. . . something in man which is always apparently on the eve of disappearing, but never disappears, an assurance which is always apparently saying farewell and yet illimitably lingers, a string which is always stretched to snapping and yet never snaps. . . the thing that never deserts men and yet always, with daring diplomacy, threatens to desert them. It has indeed dwelt among and controlled all the kings and crowds, but only with the air of a pilgrim passing by. It has indeed warmed and lit men from the beginning of Eden with an unending glow, but it was the glow of an eternal sunset.

I recently saw someone quip on Substack Notes, “we used to dream about the future; now we dream about the 90s.”4 And while I take the point (and commend its wit), I would contend that we have always dreamed about both the past and the future. Perhaps our nostalgia for yesteryear and our longing for a better tomorrow are really the same thing.

Burns’s hymn likewise speaks to this dualism. It’s not just about “times gone by” but about “times to come”:

We’ll take a cup of kindness yet,

For auld lang syne.

Perhaps a cup of kindness awaits us yet. Perhaps nostalgia and future dreams are both sehnsucht. Perhaps they are both hope. We long for a home that is both back there and up ahead. This isn’t a clean-cut, linear answer. However, when have such simple answers ever adequately captured reality? The departure-and-return is our oldest story (maybe our only one), and it’s fitting that Eliot writes:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.5

T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding” from Four Quartets.

T.S. Eliot, “East Coker” from Four Quartets.

It’s a superb essay, and yet I never see people engaging it.

If this was you, please comment. The ways of Substack Notes are, in the words of the prophet, quite literally unsearchable.

T.S. Eliot, “Little Gidding” from Four Quartets.