The Seven Lamps of Prose

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Series

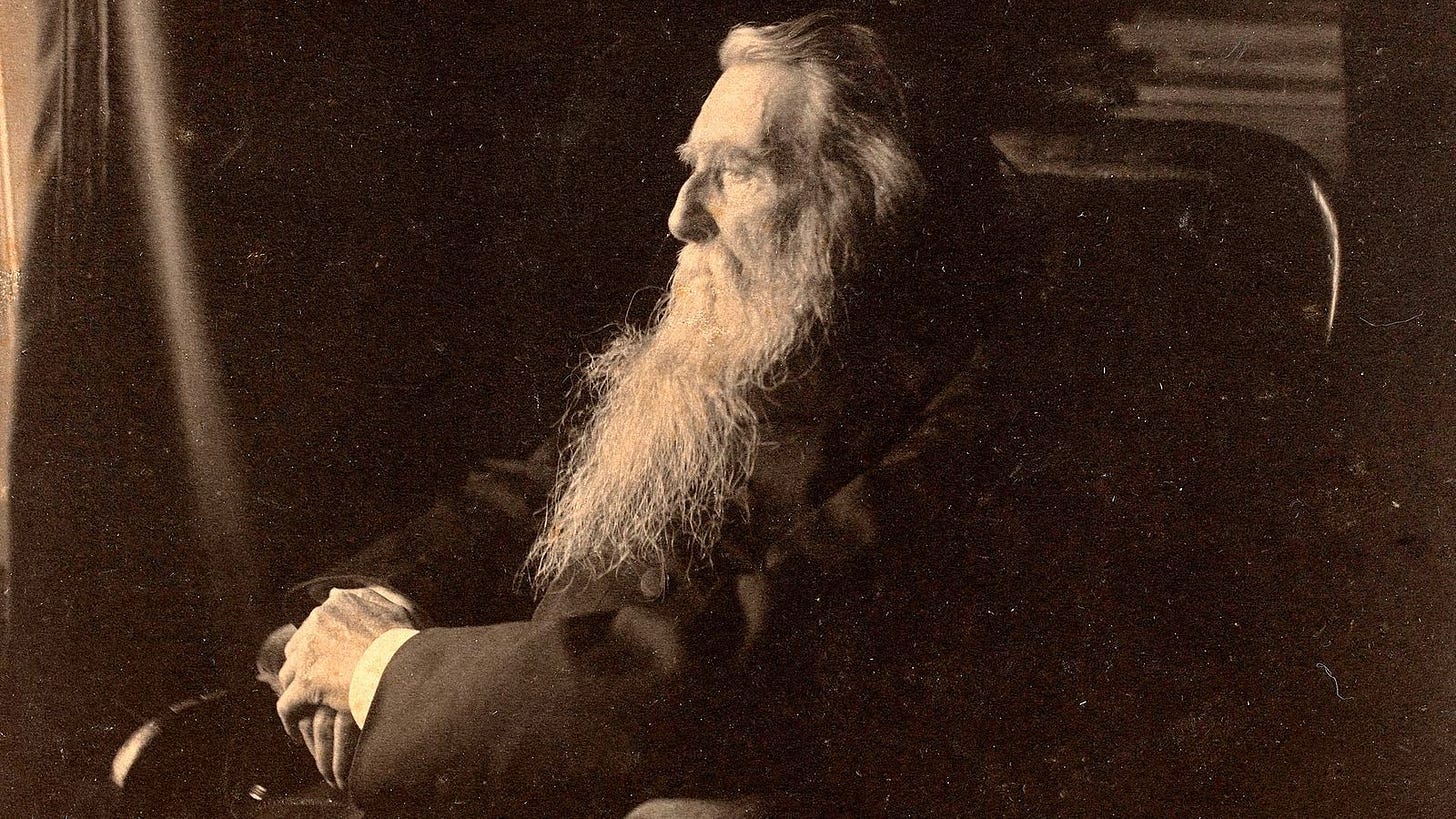

John Ruskin, born in 1819, was a British writer, artist, and critic. An adamant supporter of J.M.W. Turner and the Pre-Raphaelite movement (I have two prints from this school in my study: Edward Burne-Jone’s The Beguiling Of Merlin; Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Le Pia de’Tolomei), Ruskin became a major Victorian commentator on aesthetics. He was admired by a diverse range of nineteenth-century artists and thinkers: Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, Charlotte Brontë, Alfred Lord Tennyson, among others. His influence was - to say the least - substantial; a BBC article even asked, “Was Ruskin the most important man of the last 200 years?”

One of Ruskin’s major fields of commentary was architecture. His book The Seven Lamps of Architecture, which is technically a (very) extended essay, is an enduring look at how aesthetics are involved in this fundamental act of dwelling. Ruskin attempts to establish first principles to guide all architectural practices. He describes this intention:

“I have long felt convinced of the necessity…of some determined effort to extricate from the confused mass of partial traditions and dogmata with which it has become encumbered during imperfect or restricted practice, those large principles of right which are applicable to every stage and style of it.” (10)

His approach to architecture is couched in a larger paradigm of human flourishing. Ruskin makes a direct connection between aesthetics and our values, a view that would be attacked in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

He sought “constant laws” which would undergird all human actions, including aesthetic pursuits. Thus, in recognizing the lamps of architecture, one could also recognize “some ultimate nerve or fibre of the mighty laws which govern the moral world.” As a consequence, “every action, down even to the drawing of a line or utterance of a syllable, is capable of peculiar dignity” (12).

Regardless of one’s evaluation of his broader theory, Ruskin’s aesthetics offer an important lesson. Our art, whether in paper or stone, is inextricable from a world of human values (both in creation and reception) and is capable of deeply affecting us. Rather than being a matter of secondary importance, dealing in the currency of pure subjectivism, aesthetics is intimately involved in the broader project of being human. For good reason Ruskin connected architecture with a ‘for-the-sake-of’ paradigm, directing his own toward “that chief end of all purposes, the pleasing of God” (12).

In short, Ruskin asks us to take aesthetics seriously.

Here’s the twist.

In this series, I will outline each of Ruskin’s “lamps” and apply these aesthetic concepts to prose, attempting to sketch a corresponding “Seven Lamps of Prose.” After all, I think Hemingway was right when he famously said, “Prose is architecture, not interior decoration.” He went on to write, in a telling conclusion, that “Baroque is over.” I’m not entirely convinced of the latter.